|

By Dr. Sheila Clonan  October is Dyslexia Awareness Month. It is also ADHD Awareness month and Down Syndrome Awareness month—so much awesomeness packed into 31 little days! We’ll address those later, but in this post, we want to play a little “Did you know?” game, raise awareness of issues pertaining to dyslexia, and let local readers know about some amazing upcoming events. Did you know that at least 1 in 5 students is estimated to struggle with dyslexia, a neurological disorder characterized by difficulties with phonological processing that impair accurate and fluent decoding?

2 Comments

By Michelle Storie  So you just received your child’s State ELA or Math Assessment scores. Or your child just underwent a psychological evaluation and completed individually-administered norm-referenced tests. What do the scores mean? How do you make sense of the information provided? And what do the test results tell you? How can they help your child? In this blog, we hope to answer the basics to these questions. Standardized tests are norm-referenced tests. This means that the tests are given the same way to all children. Evaluators follow rules for test administration and are not permitted to alter materials or reword questions. This allows you to compare your child’s score to that of other individuals his or her age who were part of the norming sample. When the tests are created, they are administered to groups of students of varying ages and the results are used to determine what was considered an Average score, a Below Average score, etc. A standardized test allows you to draw a comparison between your child’s score and the scores of other individuals of the same age (or grade, if using grade-based scores). By Dr. Sheila Clonan  ..First, let’s address the issue of whether or not dyslexia is an appropriate, school-based diagnosis supported by special education law. The short answer: YES. Dyslexia is a specific presentation of a language-based “Specific Learning Disability” in Reading—the most common one, in fact. Special Education law (or IDEA) defines a specific learning disability as “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia.” (See 20 U.S.C. §1401(30) and 34 CFR §300.8(c)(10) (emphasis added). So again, yes. But... By Dr. Sheila Clonan  We’ve worked with many families lately whose schools “don’t recognize” dyslexia. They are told either that it is a “medical diagnosis” (what?!?) or that it “isn’t in the law.” We’ve had parents tell us that their school told them that their child was too young to test, or that dyslexia is just a catch-all term and there’s no test for it. None of these statements are true. Unfortunately, if your school won’t recognize dyslexia, they are unlikely to treat it effectively. Some parents have even been told that dyslexia “doesn’t exist.” However, over 30 years of scientific evidence and research supports the existence of dyslexia, as well as effective interventions for students diagnosed with dyslexia. Dyslexia is a specific neurobiological learning disability that is characterized by difficulty with accurate and/or fluent word recognition, poor decoding skills and weak spelling. Secondary problems in vocabulary, reading comprehension and writing may also develop. These are fundamental skills that must be mastered as early as possible for student success. However, contrary to what parents are often told, dyslexia is one of the most common causes of reading difficulties in elementary school children, affecting at least 5-10% of the population, with some estimates as high as 17%. Dyslexia ranges from relatively mild to more severe symptoms, so some dyslexic students may qualify for special education as a student with a learning disability, but some may not. Regardless, all students with dyslexia (indeed, all struggling readers) require intensive and explicit systematic reading intervention to progress appropriately. Unfortunately, rare is the teacher- special education, literacy, or classroom teacher—who has been adequately trained in effective, scientifically-based reading instruction.  Often, bright students with attentional difficulties “fall between the cracks” of services available in the school system. While Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is not included in the 13 disability categories covered under special education law, some students qualify for an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and special education services through a label of “Other Health Impaired.” However, in order to qualify for such services in most school systems, the student typically needs to be failing. This is not an entirely accurate interpretation of the law, however, which merely states that the disability must “adversely affect educational performance.” Nonetheless, to qualify for an IEP in most school systems, the child needs to be struggling academically and deemed to require specialized instruction (or special education). But what about the student doing “just well enough,” who manages, through extra hard work and effort—and the more-than-occasional parental “rescue” to make adequate grades? With some strong parental advocacy, that student may qualify for accommodations via a “504 Plan,” which is supported by federal civil rights law and provides accommodations to the learning environment (but no direct, or “specialized” instruction).

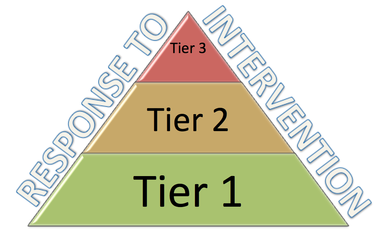

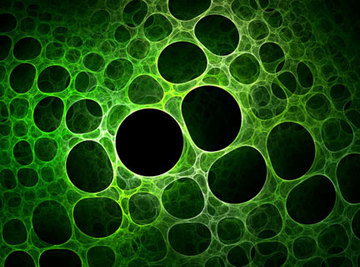

Written by Dr. Sheila Clonan  Response to Intervention, or RTI, is a three-tier process for providing intervention and supports to students prior to the initiation of any assessment for special education. The idea is that, by providing targeted, research-based interventions early, we can ameliorate relatively mild learning difficulties, thereby preventing the need for designation as a student with a disability. It began in response to an all-too-common problem—which became known as the “wait to fail” model. That is, in the past, students quite literally had to fail before they would be tested for special education and therein provided necessary intervention. Tiered levels of support like RTI, in contrast, are based on prevention models. Tier one generally consists of an effective core curriculum in the classroom. Theoretically, this will address the learning needs of approximately 80% of students. The remaining 20% will be provided with what is often called “Tier 2” intervention: intervention that targets learning in a fairly generic- but efficient- way. Let’s take the case of reading. Most schools collect progress monitoring data on all students. Then they identify a “cut-off” score that indicates the child is in the lower quartile and may benefit from Tier 2 intervention. At this stage, most schools have a ready-prepared intervention to offer. Some schools used computer-based programs, such as Fast ForWord or Accelerated Reader. Others offer an additional reading group with the school’s literacy specialist. For approximately some of the children involved in Tier 2 intervention, the additional instruction—almost regardless of the form it takes—will be enough to help them get up to speed. For children with a specific learning disability such as Dyslexia, however, such standard interventions will rarely be enough to close the gap between them and their peers. Instead, these students require systematic, intensive, phonologically-based reading instruction targeted specifically to their individual needs and administered by a highly trained instructor. Students with Dyslexia are generally missing some of the important building blocks of reading—the cognitive components that underlie accurate and fluent reading. However, they often “progress”—ie, memorize enough words—just enough to make it look like they are benefitting from the generic intervention. This makes school staff reluctant to test the child for a learning disability. But unfortunately, memorization is a very inefficient strategy- and the progress will not be enough to close the gap between the student and her peers, nor to repair the foundational skills on which on which reading is built. We often see students who have inched along in this way- progressing just enough to avoid failure, but not enough to catch up- or, more importantly, learn the skills they need to ultimately become accurate and fluent readers. These students tend to be bright, creative and hard-working. They work hard enough— and usually have enough support from their parents—that they earn passing grades despite falling farther and farther behind in their reading. They often spend hours upon frustrating hours completing homework. They tend to do poorly on tests- but excel in oral participation- or other aspects of the school day. Sometimes teachers wonder if they are making “careless” mistakes—maybe they need to slow down, “try harder”- or, my all-time favorite- “look harder.” They may be reading well enough to get the “gist” of the information—so they can maintain the appearance of being able to read enough to “keep up,” but gist reading is notoriously unreliable in decontextualized reading such as in textbooks- or worse, multiple choice tests. Often, the parents of these children have repeatedly shared concerns with school staff that “something is wrong” but been (falsely) reassured that “he’s young yet” or “she’s progressing at her own rate.” Your child is not failing, they may add, and so does not have an educational disability. While we’ve no doubt that these staff members mean well, the end result is that the student suffers for years, believing that she is stupid or slow, working hard but never managing to keep up. Finally, frustrated, parents turn to a private evaluator, seeking an understanding. They know their child is smart, they see how hard he is working, and they want to what can be done to help him. When implemented as intended, Response to Intervention can enhance student learning. The intention of the prevention process is to shift educational resources away from classification of disabilities and toward the provision and evaluation of effective instruction. Through early screening, schools can identify and provide support more quickly to struggling learners. In practice, however, the process all too often delays the provision of appropriate evaluations and services (as noted in this 2011 Memo to all State Directors of Special Education, the U.S. Department of Education). If you have concerns about your child’s educational progress and feel that school staff are delaying evaluation and support, you have the right to request an evaluation in all areas of suspected disability. Put your request in writing. See more about how to get your child evaluated in our ebook, A Parent’s Guide to Educational Assessment in New York. Written by Dr. Sheila Clonan September 27, 2015 @ 9:30 am  Recent neurological studies have given us greater insight into brain plasticity, or the brain’s ability to adapt or change in response to experience. This is the science behind such popular brain exercise apps like LumosityTM and CognifitTM that aim to re-train the brain by making new connections in neural circuits. The idea is that by engaging in intensive and repetitive exercises that are tailored for specific goals, skills like memory, cognitive processing, and attention can be improved. The jury may still be out on the effectiveness of some of these self-administered apps, but there is good research and evidence that brain plasticity is real. There is also substantial evidence that working memory, the part of the brain function that is key in handling processing, can be definitively improved through intensive intervention. This is good news for all, but especially for children who are struggling in school as a result of a learning disability that may have a direct connection to working memory. Such learning disabilities among children include ADHD, Dyslexia, Auditory Processing Disorders and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Written by Dr. Kimberly Williams 9/18/2015 at 7:18 PM Sending your child to college can be stressful enough for parents, but perhaps particularly so for parents of students with disabilities. I have worked with college students with learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD and other disabilities for several years and there are a few lessons I’ve found to be critical for a student to set herself up for success:

Written by Dr. Sheila Clonan 9/5/15 at 8:05 pm If you live in Central New York and are looking for out of school resources to have your child tested for educational issues such as learning disabilities, dyslexia, ADHD, giftedness, school anxiety, or behavioral issues, you may find the search daunting. The fact is that outside of the public school system, there is a shortage of qualified professionals offering comprehensive psychoeducational testing services for children. This is especially true in Central New York or the areas between Binghamton, Watertown, Rochester, and Utica, where specialized services can be challenging to find. I’ve had many parents tell me that they were given a list of providers by their school or physician, called all 15-20 phone numbers only to find most disconnected, no longer in practice, or not qualified to provide the desired service.

You know it’s the end of the summer when the back-to-school ads return, everyone is buying their state fair tickets (in New York), and the leaves on the trees start changing colors, which seems to be happening earlier and earlier. The back-to-school transition brings with it a lot of emotions: excitement about entering a new grade and reuniting with friends, anxiety about joining a new classroom, meeting new classmates and teachers, concern about the difficulty of the classwork or tests, and sometimes fear of separating from parents. For kids with learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, anxiety, ADHD or other disabilities, these back to school transitions can be even more challenging.

|

Our place to post news and tips about us and our educational community. Please feel free to follow or comment.

Archives

October 2017

Categories

All

|

|

Our Team

|

Our Work

|

Our Information

e-mail us [email protected]

Call Us 315-320-6404

2070 Glenwood Dr

Cazenovia, NY 13035 |

Educational Solutions CNY is a coalition of educational consultants. Each consultant is practicing under their own license or business.

© 2021 Educational Solutions CNY. All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed